Will a megathrust earthquake strike the NW in 2013? Some clues emerging

There were 4,800 earthquakes in the Northwest in 2012 and a record "episodic tremor and slip" event – a string of deep mini-quakes running from Vancouver Island to below Centralia – over the summer, but does any of that mean we're likely to see the "big one" in 2013?

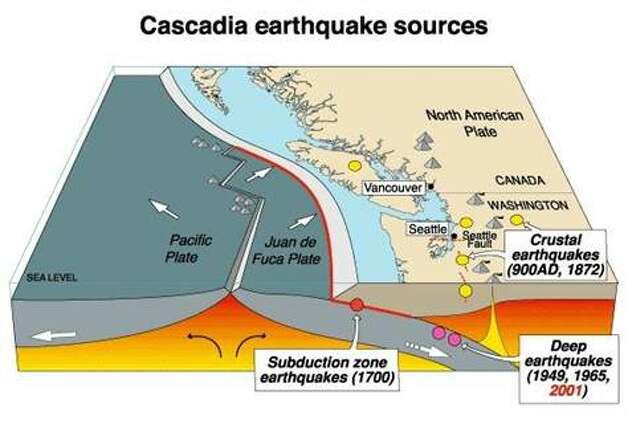

While the devastating megathrust quakes that happen every 300 to 500 years in our neck of the woods (those caused by the Juan De Fuca plate's grinding collision and subduction with the North American plate) are still impossible to predict, some clues may be emerging.

An immature science

An immature science

Taken together, last year's quakes were "mild" since so few of them were big enough to be felt, said John Vidale, director of the Pacific Northwest Seismic Network.

The biggest and most interesting quake of the year struck under Victoria, B.C., last week. It was a magnitude 4 temblor and resembled in depth and fault the magnitude 6.8 Nisqually quake that damaged Seattle and shook the region in 2001, he said.

It was felt and reported to the network's webpage by about 800 people.

He added that a string of unusual quakes around the globe has the seismic community baffled. A big earthquake off the coast of Sumatra in the Indian Ocean six months ago was "very strange" because of its size and distance from the plate boundary.

It showed "we can get earthquakes we really hadn't anticipated," he said.

In the past few years, China got hit with an earthquake on a fault that wasn't mapped, New Zealand suffered a "very rare earthquake" ...

"There's a whole series of events in the last decade that give us the impression that we know less than ever," Vidale said. "We keep thinking that these are the specific risks we need to look out for and then earthquakes happen that aren't the ones we thought were most likely to happen."

Also, a roughly annual seismic event in the Northwest discovered 12 years ago – the "episodic tremor and slip,"or ETS – went wild last summer.

Doing the 'tremor and slip'

The boundary between the Juan De Fuca plate offshore and the North American plate runs under the Puget Sound area from California up to Canada. That's where we get the megathrust quakes of magnitude 9 or better. Below that danger zone, deeper in the subduction, is where the ETS happens.

The tremor and slip this summer was "one of the biggest ETS events yet monitored," the seismic network reported in its blog. And that had the experts "ever so slightly nervous."

"We thought we knew the pattern pretty well, that it would start down in the south Puget Sound, spread out for a couple of weeks, mainly going north under the Vancouver Island," Vidale told KPLU in October. "This time broke the pattern ... It started in the north and came south. It is also the biggest episode we've seen yet."

Clues to the big one?

"These are adding stress to the area where we expect damaging earthquakes to occur," said Stanford University geophysics professor Paul Segall, "... so what does that mean? What do you do from a practical standpoint?"

When the ETS was first discovered, officials in Canada sent out earthquake warnings when one fired up because they worried these events signaled a potential quake. After a string of false alarms and new mysteries, they've stopped the practice.

However, the question remains: Are these events associated with earthquakes and if so, how?

Segall is building computer models to find answers and so far has some preliminary results that suggest the tremors and slips are in fact connected to quakes. In his simulations, after a big earthquake, the events stop for about 100 years and then start up again.

And then one of them eventually will "spontaneously grow into a fast, dynamic rupture" – an earthquake. The problem is he can't tell which one will mutate into disaster.

"You would hope that there would be something about them that would tip us off that we're getting near the end of the cycle and there was a big earthquake about to occur," he said. "In these simulations, we don't see anything in and of itself that presages an earthquake."

A fascinating time

Segall's initial results were announced by Stanford under the title "Himalayas and Pacific Northwest could experience major earthquakes, Stanford geophysicists say."

The release explains:

The Cascadia subduction zone, which stretches from northern California to Vancouver Island, has not experienced a major seismic event since it ruptured in 1700, an 8.7–9.2 magnitude earthquake that shook the region and created a tsunami that reached Japan. And while many geophysicists believe the fault is due for a similar scale event, the relative lack of any earthquake data in the Pacific Northwest makes it difficult to predict how ground motion from a future event would propagate in the Cascadia area, which runs through Seattle, Portland and Vancouver. ...

The work is still young, and Segall noted that the model needs refinement to better match actual observations and to possibly identify the signature of the event that triggers a large earthquake.

"We're not so confident in our model that public policy should be based on the output of our calculations, but we're working in that direction," Segall said in the release.

One thing that makes Segall's work difficult is a lack of data from actual earthquakes in the Cascadia region. Earlier this year, however, earthquakes in Mexico and Costa Rica occurred in areas that experience slow slip events similar to those in Cascadia.

"There are a few places in the world where these slow slip events are associated with small to moderate-sized earthquakes, and they are very clearly tied in space and time," he said. "The timing is clear, not a coincidence. They really occur in lockstep."

So, the research goes on and both Vidale and Segall said they need more data collection instruments stuck in the ground around the globe to create data sets that will solve these puzzles.

"One of the things about the ETS events is that it is a reminder every 15 months or so in the Puget Sound region ... something is happening down there, and it's pushing stress around and it's just a reminder that (a megathrust earthquake) is inevitable. It's not if it's going to happen it's when. It's probably not too soon, but we can't be too sure of that." SeatlePI